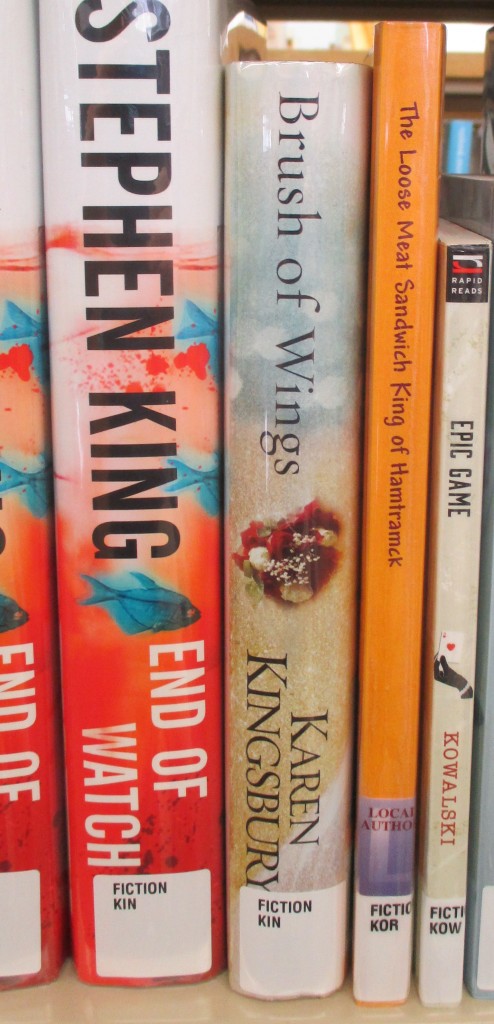

How many different kinds of hyphen keys are on your keyboard? (That top one is the underscore.)

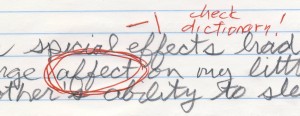

When it comes to punctuation, the less the better. Period, comma, question mark, exclamation mark, quotation marks. That’s it. Semicolon? I never saw a sentence with a semicolon that wasn’t really just two sentences. Apostrophe? You know where I stand on those. Get rid of them. Colon? At the beginning of a list, OK. But does it really add anything? I think we could dump it and nobody would miss it.

How about the hyphen (what was called a dash when I was in school)? That one is still useful, although with word processing apps cleaning up our margins, we don’t need it so much for splitting words at the end of a line. The dash comes in handy for connecting words together that aren’t officially joined together in the dictionary yet, like: (do I really need this colon?)

ex-wife

one-fourth

super-expensive

I also like to use a dash to indicate an unfinished or interrupted sentence.

“Now I can reveal to all assembled here that the murderer’s name is – ” Mr. Stones said, just as a shot rang out.

The human brain – and I mean this in all seriousness – is not as necessary as you might think.

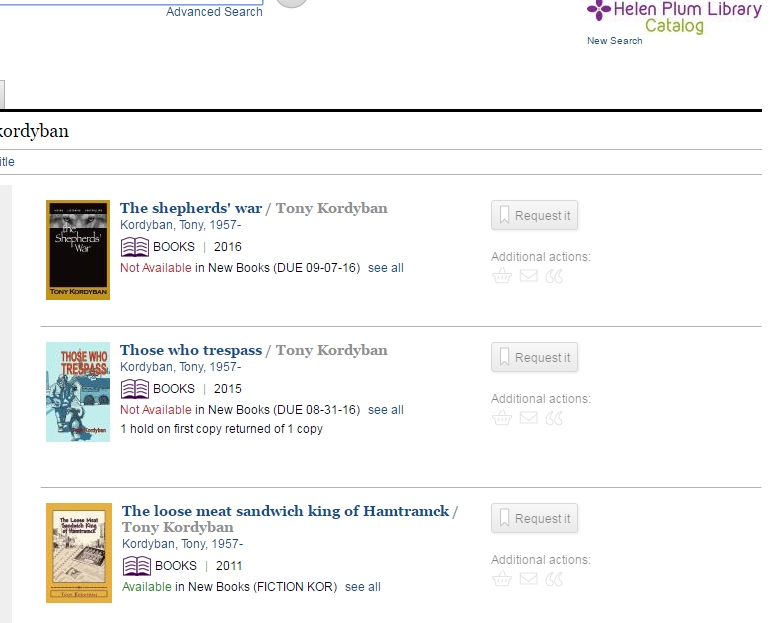

The dash and the hyphen are the same thing. But did you know that according to English style guides (such as The Chicago Manual of Style, or The AP Stylebook), that there are actually three different kinds of dash, and each one has its own unique usage and meaning?

dash: the shortest version of this little horizontal line. It is used for connecting compound words and for denoting the minus function in arithmetic

en dash: a little longer than the dash. It is the width of the letter “n” and that’s where it gets its odd name. This extra length is supposed to indicate that it stands for missing things in a series.

January-June means only the months of January and June and nothing in between.

January–June mean all six months. So If I live in Building 5, and I get a memo that says mail will be delivered to Buildings 4-7, I need to get out a ruler and measure the length of the dash to find out if I will be getting my mail. Really?

en dash is also used to connect compound words that don’t have dashes in the main body of the original word. I can’t even explain what that means except by showing this example:

Joey is a post–Iraq War veteran.

Iraq War is a compound word connected by a space, so when I add the prefix “post” to it I am supposed to use an en dash instead of a hyphen. This rule seems a little obscure to me.

em dash is a dash the size of the letter “m”. Depending on what font you like, the letter n and letter m can be exactly the same width, so that doesn’t necessarily help you figure out which size dash you have. Em dashes, according to the style books, are used for:

indicating the positions of missing letters in words, as in “F — — K ” when you want to be polite and not directly spell out “FINK”. Although it seems as if the underscore or asterisk has taken over this function in the last fifty years or so

showing a break in a sentence, as in “I’d better not get too close to the edge of this — !” The style books say in this situation you’re supposed to use two em dashes. Maybe they think nobody will be able to recognize the em dash by itself and not understand the sentence, so throw in a spare to get the true meaning across.

as a bullet in a bullet list. Again, there is no reason why you have to use a slightly longer dash to accomplish this.

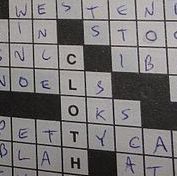

When you put them side by side, you can probably tell the difference between the dash, the en dash and the em dash.

hyphen-dash en–dash em—dash

But when there is only one of them on the page, how do you know which one it is? It takes an expert typographer and a jeweler’s loupe to be sure. And in the long run, does it truly add any meaning to the words? There is no confusion when you see

PappaG is a master of the post–hip hop genre.

instead of

TJoe didn’t know there even was a post—hip hop genre, or what the word genre means.

The length of the dash doesn’t send you running to a dictionary or to Google Translate. It doesn’t even slow you down. The truth is we don’t need three kinds of dash. Pick one and use it for everything. Isn’t that why there is only one dash key on the keyboard?

It’s like having three kinds of question marks, each one progressively curlier than the first. The first one ends ordinary questions, the second is only for rhetorical questions, and the third only to indicate Upspeak. (Upspeak is the annoying speech pattern in which the speaker ends every sentence with a rising pitch, so that every one of them sounds like a question, but most often is not.)

It would be pointless and confusing to have three question marks. It is pointless and confusing to have three kinds of dashes, and to tell people they are idiots when they use the “wrong” one.

You got that, Stylebooks? Make English easier — — not harder for us to get right. (Maybe those double em dashes should have been a semicolon?)