Answers to those Doggone Thermal Design Questions

By Tony Kordyban

Copyright by Tony Kordyban 2001

Dear Doggone,

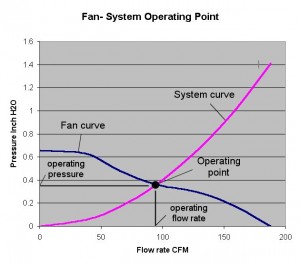

From the picture of the coffee-stained napkin on the cover of your book, I am now familiar with the method of figuring out the operating point of a fan. You figure out the flow rate vs. backpressure curve for your system, and then you plot it against the flow rate vs. pressure performance curve of the fan, and where the two curves cross is the operating point. That seems pretty simple.

But my fan is too noisy at full speed. Most of the time, I don’t need it to run at full capacity. I only need it to go full blast when the room temperature goes over 40 degrees C. Maybe I could put in a speed controller to slow the fan down when I don’t need all that air, and a thermal sensor to tell it to speed up again if the room gets hot. Slowing the fan down will definitely make it quieter. Before I do that, is there a way I can calculate the new operating point at reduced fan speed? And how much does the audible noise go down with reduced fan speed?

And is all this stuff about fans in your book? I haven’t taken off the clear plastic wrapper yet, because the bookstore said I couldn’t get my money back if the seal was broken. So far the cover has been pretty useful, but I think I need just a little more to judge it by.

Penurious in Pensacola

Dear Penny,

There are three tools that you could use to solve this problem:

- A flowbench. With this chamber made of a variable-speed blower, calibrated flow rate measuring orifices, and air pressure sensors, you can measure the flow rate vs. pressure of a fan at any speed, or you can measure the system curve of your electronics box. OK, I don’t have one either.

- A telephone. Call your fan vendor. Many times they have the fan curve you are looking for in their files. They don’t publish everything in their catalogs. Demand fan curves at all possible fan speeds. If your purchasing department has forced you to buy from the lowest bidder, you might have to learn a few phrases in Korean or Chinese before you make your calls.

- The Fan Laws. These are a set of equations based on dimensional analysis and fluid dynamics theory. Unlike the laws made by legislative bodies, they actually make sense.

If you know the performance data for a particular fan under one set of conditions, the fan laws can be used to estimate the fan performance under another set of conditions. For example, the curve in a fan catalog is based on sea level altitude testing. How will that fan behave inLeadville,Colorado, at 10,000 feet, where the air density is only about 74% of its value at sea level? Off the top of my head I’d say — I’m not sure. That’s why I’m glad I have the fan laws to tell me.

| air flow rate in cubic feet per minute (although any units for volume flow rate can be used) | |

| fan rotation speed in revolutions per minute (again, any consistent units will work, because it is only a ratio of speeds) | |

| air pressure | |

| fan motor power | |

| audible noise of the fan, measured in one of the typical log scales, such as Sound Pressure Level or Sound Power Level |

I copied this table out of an old Comair Rotron catalog. I don’t think they invented the fan laws, so I hope they won’t complain if I publish them here. (By the way, this is NOT in my book. But open it anyway. There is a good story in it about how wind chill factor is related to TV ratings.)

Let’s get back to your particular problem, Penny. You have a performance curve for a fan at full speed. You want to know how the fan curve changes if you reduce the rotational speed (RPM), and you’d also like to know how much the audible noise will go down. Pick points from the existing fan curve, plug them into the fan laws, and re-draw your new fan curve. Here is an example:

Let’s say you want to reduce speed from 2000 to 1500 RPM. At one point on your full-speed curve, the flow rate is 50 CFM and the pressure is 0.3 inches of H2O.

CFM 1500 RPM = 50 * (1500/2000) = 38 CFM

P1500 RPM = 0.3 * (1500/2000)2 = 0.17 inches H2O

Remember to apply this to both the flow rate AND the pressure for each point on the original curve.

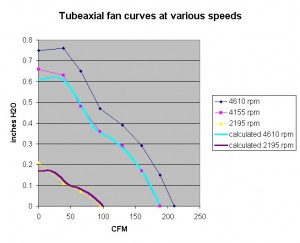

How good are the fan laws? I don’t have personal experience with the power or audible noise scaling equations, but here is an example of flow rate and pressure scaling with fan speed.

I happened to have a data sheet for a real fan that gave the fan curves at three different fan speeds. I used the fan laws to calculate the fan curves for the two slower speeds from the maximum speed curve. Take a look and tell me how well the fan laws predict the data.

The curves with markers on them are lab data. The solid lines are my fan-law-calculated curves. I was so impressed with the agreement, that I accused the fan vendor of fabricating the low speed data using the fan laws themselves.

The fan laws are about as good as you will get for any calculated result in the field of electronics cooling (which isn’t saying much). My grad school heat transfer professor was fond of saying we were doing a good job to predict temperatures within plus or minus 25% of the right answer. Eventually you will have to build something and test its performance. At least using these equations will get you close to what you want before you start bending metal and melting solder.

.

———————————–

Dear Cooling Guy,

Wouldn’t it be great if the Electronics Cooling CFD vendors would include the fan laws in their software? They already allow you to specify a fan curve as part of the model, or even to import one from a fan library. I think it would be a cool feature if you could dial in whatever RPM you want, and the software would automatically modify the standard fan performance curve, based on the fan laws. How do we get them to do that?

paul

Dear Paul,

Sounds like a great idea. There could even be a slider bar called RPM in the Fan Construction menu. As you slide it up and down, the fan curve would shrink and grow. It might even allow you to model thermostatically controlled fans automatically.

I will put that on on page 27 of my list of things to tell the CFD people the next time I see them.

—————————————————————————————–

Isn’t Everything He Knows Wrong, Too?

—————————————————————————————————————

The straight dope on Tony Kordyban

The straight dope on Tony Kordyban

Tony Kordyban has been an engineer in the field of electronics cooling for different telecom and power supply companies (who can keep track when they change names so frequently?) for the last twenty years. Maybe that doesn’t make him an expert in heat transfer theory, but it has certainly gained him a lot of experience in the ways NOT to cool electronics. He does have some book-learnin’, with a BS in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Detroit (motto:Detroit— no place for wimps) and a Masters in Mechanical Engineering from Stanford (motto: shouldn’t Nobels count more than Rose Bowls?)

In those twenty years Tony has come to the conclusion that a lot of the common practices of electronics cooling are full of baloney. He has run into so much nonsense in the field that he has found it easier to just assume “everything you know is wrong” (from the comedy album by Firesign Theatre), and to question everything against the basic principles of heat transfer theory.

Tony has been collecting case studies of the wrong way to cool electronics, using them to educate the cooling masses, applying humor as the sugar to help the medicine go down. These have been published recently by the ASME Press in a book called, “Hot Air Rises and Heat Sinks: Everything You Know About Cooling Electronics Is Wrong.” It is available direct from ASME Press at 1-800-843-2763 or at their web site at http://www.asme.org/pubs/asmepress, Order Number 800741.