English rules are so unfair.

Nobody at all is ever confused by the built-in contradiction between these two sentences:

The mail carrier came through the door to give me a package.

The Incredible Hulk came through the door to give me a pounding.

The first example evokes an image of a uniformed postal character walking through an open doorway carrying a cardboard box, possibly with the Amazon logo printed on the side.

The second example makes you immediately envision a shirtless, green bundle of muscles smashing through a closed door, splinters and hinges and knobs flying in all directions.

What is the contradiction that causes no confusion? We easily interpret these sentences so automatically that we don’t even see there is a problem. The potential for confusion is that these two examples use the word door in opposite and complementary ways. Door has two definition:

- an opening in a wall or barrier; more specifically, a doorway

- the movable panel that blocks the opening in a wall or barrier

We don’t get confused, because the concept of a door is actually bigger than either one of those definitions. It includes both of them, but what it really means to us is:

a place in a wall that can either be open to allow going through, or closed to stop somebody or something from going through.

A door is not just the hole in the wall, or just the wooden panel smashed by The Hulk. A door is the thing that allows the passageway to be open OR closed. Nobody is confused when we call an opening a door, and the very next minute we call a glass panel on hinges a door.

The English language is full of words that stand for a big concept that include their own opposites. Don’t rack your brain to think of them. It’s hard, because it is so basic to our natural ability for language that we don’t think about them consciously. Ponder these examples:

This restaurant serves soft-shelled crab.

The walnuts had to be shelled before adding them to the salad.

(For those who don’t cook, or maybe even don’t eat, the crabs are cooked with the shell ON and the walnuts are taken OUT of their shells. Both use the word shelled, even though they have opposite meanings.)

Another one that rhymes with shell, by coincidence, is:

Yuck! Your dog sure smells!

Hooray! Your dog smells pheasant from half a mile away. We’ll bag our limit this season.

You get it by now. One simple word covers the whole topic of emitting or detecting odors. The few times this is not clear by context, we get a pleasant joke out of it (see Monty Python’s “Killer Joke” sketch.

The Unfair Part

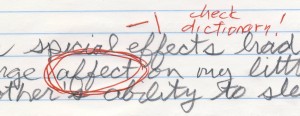

Everybody is used to the idea that one simple word can represent a complex concept that contains opposite meanings within it, the way a single penny can be both Heads and Tails. But the Grammar Police insist that there are also sets of words that are very closely related, and separated by only one or two letters in spelling, and may even have nearly the same pronunciation, and if we use the wrong one, we are penalized and branded as illiterate. Here is a famous example from the Grammar Police Code. Don’t mix them up or you will be smacked on the hand with a wooden ruler:

affect/effect

Each of these words has its own very specific definition. The problem is that they are opposite sides of the same concept, and they sound almost the same unless you exaggerate the sound of effect by adding a long-E at the beginning, and so nobody can really remember which one to use in a particular situation. Which one of these sentences is correct?

- The sudden appearance of The Hulk in my office affected my sense of well-being for the rest of the afternoon.

- The delivery of the package did not have nearly the same affect on my mood, even though I’d been waiting for it all morning.

Number 1 is correct and Number 2 is wrong. Affect mean to cause a change. Effect is the change itself. The effect The Hulk had was to affect my emotional state.

Confusing? I’m not surprised. It is more natural for our brains to think of the larger concept and not even need to have different words for each side of the coin. I have already used a word that has the same meaning as affect and effect and it incorporates the definitions of both of these supposedly different words: change. Change can be the cause of the differences, or it can be the difference itself.

- The Incredible Hulk changed the decor of the office to Early American Shambles.

- It took me nearly forty-five minutes to get used to the changes, especially the fist-shaped windows.

See? No confusion, even though I used only one word for both meanings. The Grammar Police would insist the reason they slap us when we use the wrong word is that it causes confusion for the reader. My point is: No, it doesn’t. The confusion comes when our natural language skills come into conflict with the artificial rules of the Grammar Police. We know instinctively that these two words should really be only one word.

When I get to be in charge of the Grammar Police, effect and affect will be merged into the single word we already think they are. I’m open to suggestion as to how to spell it. When I’m done fixing all the problems with spelling I will worry about that one.